It’s a scenario every school fears yet needs to be prepared for. An armed gunman enters the campus and begins shooting. Teachers and students panic as they try to escape from harm.

Amid the emotional chaos, how can decisions be made in real time to save lives? How can school officials and first responders receive accurate information about the shooter to create a potential path to safety?

Led by Associate Professor Subhadeep Chakraborty, a team of researchers from the University of Tennessee, in partnership with Iowa State University, have developed Active Shooter Tracking and Evacuation Routing for Survival (ASTERS) to try and find a better solution using artificial intelligence (AI) and social engineering.

The research received initial funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF), and recently gained more funding from SENTRY (Soft Target Engineering to Neutralize Threat RealitY), a Department of Homeland Security center of excellence led by Northeastern University.

The ASTERS system consists of a group of cameras and computing devices. ASTERS uses “computer vision” to locate and identify the shooter, then employs AI and social engineering to help people exit the area without crossing paths with the armed individual. The system must account for a variety of human factors, including ages, abilities, and the speed of individuals, to provide the safest and most efficient route to safety.

Real-time suggestions are provided through dynamically updating signs, which continuously receive information from the cameras and computers running the ASTERS software. X is for STOP, and arrows point teachers, students, and staff to the safest exit. If the shooter moves, arrows will change direction to point them away from the shooter.

“The basic purpose of ASTERS is to act as a decision-making support system in real time,” Chakraborty said. “We asked ourselves, how can we give people accurate information about where the shooter is and what they should do to stay safe? How can we avoid crowding near exits? Another aspect is how to give that information to the first responders and the school administrators who need to make critical decisions and are going to intercept the shooter.”

Addressing a Growing Problem

Once an uncommon worry, the number of school shootings in the United States has skyrocketed in the last decade. They have risen from 41 total K-12 school shootings in 2015 to an all-time high of 348 in 2023, according to the K-12 School Shooting Database compiled by David Riedman.

Finding a way to keep children and teachers safe from harm has been a pressing issue. UT’s group believes ASTERS can help solve some of the problems inherent with relying on panicked witnesses at the scene of a shooting. Rather than word of mouth, ASTERS provides a snapshot of the shooter’s face, the kind of gun the shooter is carrying, and the shooter’s location.

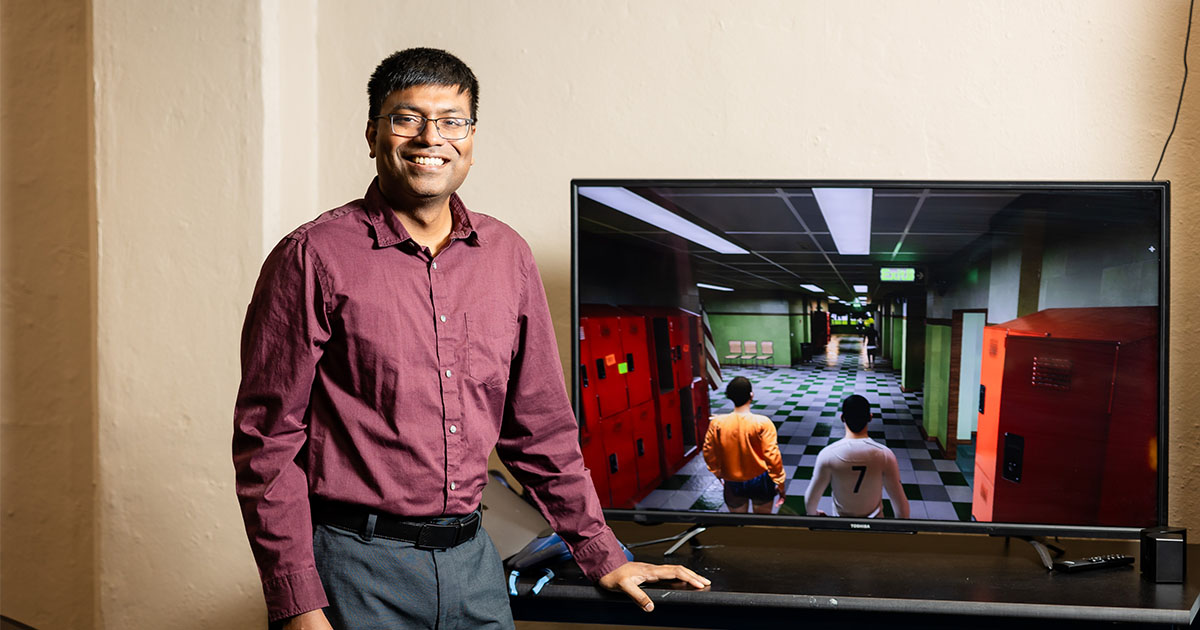

The ASTERS research team has developed a digital twin, which is like a hyper realistic video game of the system that portrays the ASTERS technology. It allows them to run the algorithms with images.

“This is the best way we can test our algorithms, with the digital twin allowing for simulating real concerns such as people getting stuck in doorways, creating bottlenecks. These tests give us more confidence in the processes that are going on at the back end,” Chakraborty said. “The other thing the digital twin helps with is just visualization – it shows people clearly what is happening. It’s the closest thing to real life.”

Bringing it to Market

The SENTRY funding provided to the research team will help bring ASTERS to market. If the system goes to market, a school could purchase several cameras along with edge computing devices and several dynamic signs connected wirelessly to a server running the ASTERS algorithm in the backend.

“Every school or every office don’t have the exact same protocol to follow when an actual event unfolds,” said Graduate Research Assistant Aniirudh Ramesh, who is spearheading the business side of ASTERS. “We as researchers are essentially trying to find out if the current protocols that are being followed can be improved using modern techniques in AI. Our hope is to bring forward a product, where the mathematical and computational aspects are never apparent to the user but are hidden behind a simple interface leading to a more streamlined response to these events.”

UT’s group wants the ASTERS technology to be completely invisible at a school, unlike a reinforced backpack or a metal detector at an entrance. It wants students and teachers to feel safe without seeing a constant reminder of potential harm.

Although he is proud of the research done at UT to create ASTERS, Chakraborty hopes that ASTERS never needs to be used except in drills.

“It goes without staying, but I don’t want it to ever be used,” Chakraborty said.

Contact

Rhiannon Potkey (865-974-0683, [email protected])