In the Lab and on the Stage

As a high schooler, Sai Rangoon visited Johns Hopkins University in Maryland and fell in love with the idea of medical research.

“I was fascinated by everything,” she recalled. “I knew I wanted to come back someday to earn my graduate degree. I became super set on pursuing medicine and becoming a doctor.”

Rangoon returned to her hometown of Hyderabad, India, and began working toward a premed undergraduate track. It was a logical choice for someone who had always enjoyed math and science, attended robotics workshops, and competed in trivia competitions.

No matter how intense her career preparations became, though, Rangoon also remained devoted to her passion for Kuchipudi, a form of classical Indian dance.

“It’s therapeutic to go dance and learn something new—something different from regular academics,” said Rangoon, now a senior in the Department of Biomedical Engineering. “It’s also empowering to take the discipline that the dance form embodies and incorporate it into other aspects of my life.”

Despite her single mother’s demanding schedule, which sometimes made it difficult to see Ramani Siddhi, Rangoon’s guru (dance teacher), Rangoon still danced Kuchipudi for an average of four hours a week starting at age five.

Then, in 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic made it impossible to visit the dance studio. As Rangoon waited impatiently for things to return to normal, her career aspirations shifted.

“I felt like there were doctors everywhere on the front lines, but we were all waiting for somebody on the back end to develop the vaccine,” she said. “That’s when I decided I wanted to work on the back lines of the medical industry.”

As she investigated different career paths, Rangoon realized that biomedical engineering would let her apply her love for physics and mathematics to the medical field. The hands-on nature of the profession also appealed to her as a way to integrate physically intuitive ideas with science.

She came to the University of Tennessee in the fall of 2022 and immediately became deeply involved with Manthan, UT’s Indian Student Association, which became her home away from home. She performed Kuchipudi at two of the organization’s Diwali celebrations and served as its president her sophomore year.

Now in her final year at UT, Rangoon is working a co-op at Siemens Healthineers and serving as the treasurer of UT’s chapter of the Biomedical Engineering Society.

“I probably wouldn’t be as confident as I was in pursuing engineering if not for the confidence, patience, perseverance, discipline, and inner peace that Kuchipudi brought me,” she said. “It’s like, ‘Hey, if you can perform for a crowd of people, you can also do this.’”

Self-Expression and Research

When she was five years old, Rangoon’s mother enrolled her in many types of lessons, but Kuchipudi—a form of classical South-Indian dance in which performers use their movements and facial expressions to tell stories—was the one that most resonated with her.

“With Kuchipudi, it’s like your thoughts and emotions find a physical form. That mind-body connection, where whatever we think and feel can be put out into the world, is what kept drawing me towards Kuchipudi,” Rangoon said.

After moving to the US, Rangoon had to give up lessons with her original guru. However, she continued practicing on her own, dancing at home to unwind from school stress.

“It’s fun and therapeutic,” she said. “I feel like I’m in a safe space where I can express myself the way I am. It’s something close to my heart.”

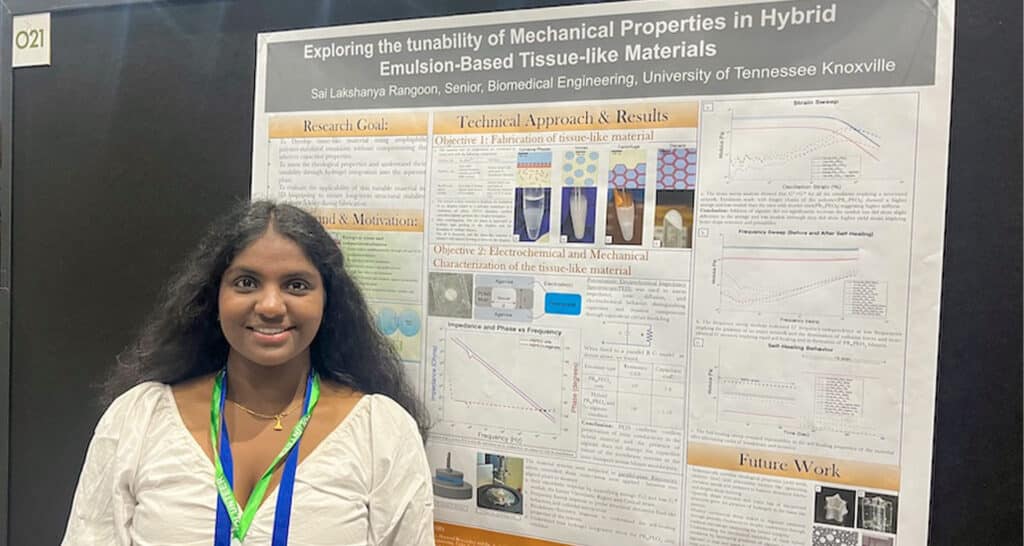

In place of formal dance lessons, Rangoon filled her time with classwork, student organizations, and lab research. She recently completed a project in the lab of UT Professor Andy Sarles, which she presented at the Biomedical Engineering Society’s 2025 Annual Meeting in San Diego this October.

While constructing artificial tissues from polymers, Rangoon found that adding alginate, a hydrogel, to the tissues enhanced their ability to self-heal after experiencing high amounts of strain. She and her lab mates have begun bioprinting the strain-resistant tissues in useful and intriguing three-dimensional shapes, like a star-shaped tunnel.

This past May, she started a systems engineering co-op with Siemens Healthineers, a medical technology company with a research branch in Knoxville. Among other responsibilities, Rangoon’s focus during her co-op is developing a device that will improve image clarity from positron-emission tomography/contrast tomography (PET-CT) scanners.

“When a patient is on a scanner, they have to breathe, but it’s harder to get a clear image when something is moving,” Rangoon explained. “The scanner’s respiratory gating system analyzes the breathing patterns of the patient and then corrects the image.”

Rangoon and her fellow co-op member have been tasked with finalizing a mechanical system that moves a patient model within the scanner in a way that mimics the movement of a breathing patient’s chest. That system will be combined with patient “phantoms” and inserted into PET/CT scanners to test and improve their correctional software.

Whether she is conducting biomedical research at the micro or macro scale, for fundamental research or patient-facing tools, Rangoon says much of her workflow is reminiscent of Kuchipudi.

“In a dancer’s mind, the performance is very chronological; you know each step in sequence, so you start with a list of all the things you have to do for the act,” she said. “That understanding made it easier for me to think through and perform experiments and other things in sequence. That clarity and confidence in thought and action are tremendous; that’s what Kuchipudi taught me more than anything.”

Contact

Izzie Gall ([email protected])